Fleeting Moments in an Infinite Flux: Artists and Other Windows on Eternity

Last December, on the same trip to SFMoMA I blogged about earlier in reference to Emily Jacir’s Where We Come From, I also saw a photography exhibit called Brought To Light: Photography and the Invisible, 1840-1900. At the time I knew I wanted to write something about it, but I had to let the idea kick around for awhile.

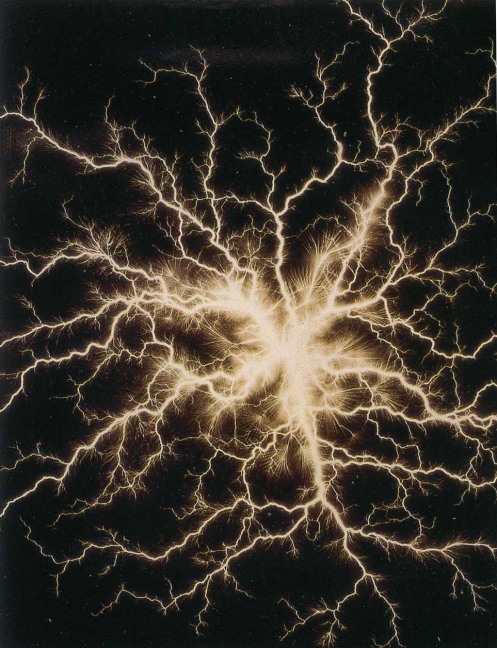

Etienne Leopold Trouvelot. Direct electric spark obtained with a Ruhmkorff coil or Wimshurst machine, also known as a "Trouvelot Figure." Photograph, c. 1888.

Brought to Light was a visual feast of early photographic images of objects and phenomena that had previously been invisible to the human eye: electrical sparks, eclipses, x-rays and movement studies. I bought the gorgeous exhibition catalog and spent some time letting these images soak into my life. Finally, they worked their way into an essay for Matthew Offenbacher’s local art ‘zine La Especial Norte, where I used Trouvelot Figures like the one pictured above to make a case about perception, channelling, and the nature of the creative act. LEN #3 hit the streets last weekend, and if you’re in Seattle, you really must pick up a free copy. (They are currently stacked at a number of contemporary art venues around the city.)

This is a fascinating synchronicity—as fellow blogger and LEN contributor Joey Veltkamp pointed out to me this morning—because today Tyler Green posted an insightful writeup about Brought to Light on Modern Art Notes that brilliantly sets the stage for my own essay, which I have posted below in its entirety.

Fleeting moments in an infinite flux: artists and other windows on eternity

by Emily Ann Pothast

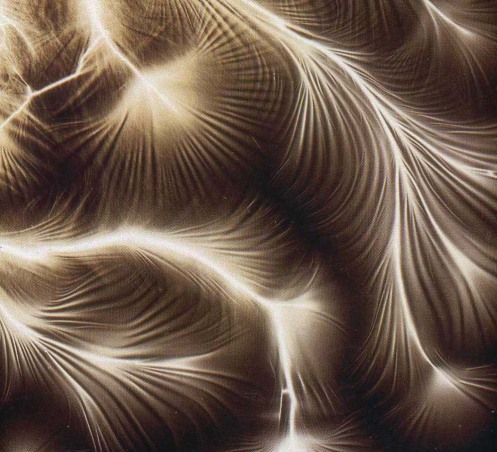

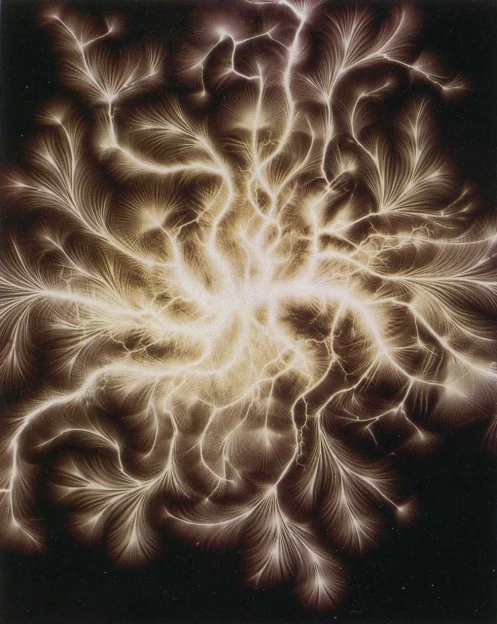

In the late 1880s, the French astronomer and artist Etienne Leopold Trouvelot created a series of photographs of electric sparks. Perfecting a technique pioneered by another scientist a few years earlier, Trouvelot generated his images without a camera, directly exposing photosensitive plates to brief bursts of electrical energy. The resulting snapshots reveal forking, infinitely self-similar patterns that resemble tree branches, rivers, vascular systems, coral, neurons, city maps, mountain ranges, microchips, mycorrhizal networks, galaxies, flow charts, family trees and feathers—basically everything in the universe whose structure is determined by growth, movement or the transfer of energy.

Trouvelot Figures (as they are called) do not begin to reveal the entire truth about the patterns they illuminate. As two-dimensional images, they can only capture fleeting moments in an infinite flux, yet they offer windows into eternity. Their fractal sinews whisper volumes about time, energy and movement; their interference patterns reveal multidimensional glimpses of infinite possibility. The paths traveled by electrical sparks adhere to rules so specific and recognizable as to seem built into the very order of the cosmos, yet in their constantly shifting, endlessly splintering movement they echo Heraclitus’ ancient admonition that change is the only certainty.

Like many viewers, I am irrepressibly drawn to patterns like Trouvelot Figures. The reason for this may be as natural as the figures themselves. Just as our immune systems have evolved as a highly adaptive mechanism for discerning “self” from “not self,” our brains appear to be innately capable of recognizing representations of the kind of patterns we’re made out of as beautiful.

Since the 1960s, Semir Zeki, a professor of neurobiology at University College, London, has been a pioneer in the field of neuroaesthetics, the study of a physiological basis for creative behavior and the experience of aesthetic enjoyment. For Zeki, the aesthetic impulse is a given—a natural funcion of the human organism like growing fingernails or fashioning mythologies. According to Zeki, the natural enemy of creativity is censorship—of which self-censorship is the most deleterious strain. Self-censorship may arise in the form of internalized social constraints, taboos, or the intellectual tendency to overwork an idea to conform to a shifting mental image. To support his case, Zeki points to research linking expert jazz improvisation to extensive dissociation and deactivation of specific areas of the prefrontal cortex. Though no causal relationship is implied, there is a correlation between turning off a self-censoring part of the brain and turning on the ability to channel artistic content from the subconscious.

The poet Gary Snyder wrote that artists are born with the gift of a “mirror of truth” that allows us to reflect things as they truly are. It would certainly appear, at least from a neurobiologist’s standpoint, that Snyder’s metaphor is not far from the mark. If we recognize ourselves as part of some infinitely changing yet formally deterministic structure (rather than discrete, isolated instances of whatever it is we are) then we may also see our creative process reflected back at us from Trouvelot’s striking images. Like a snapshot of a spark, every object of human artifice is both an idiosyncratic cross-section of a creative impulse in a particular place and time and part of an endless trajectory of causes and effects.

But what about the problem of censorship, the kind Samir Zeki finds so threatening to creativity? A strong case could be made that a certain amount of self-editing is necessary to make thoughtful, refined art. So how can we tell when our self-editing becomes censorship? Or if we are hindering ourselves from using the powers we have been given to their highest potential?

Through my own practice, I am coming to identify the difference between censorship and self-reflection as the difference between forcing and channeling. Forcing is trying to make something work that doesn’t want to. Channeling is identifying what wants to work and creating conditions that help it happen. There is a Kabbalistic concept called tzimtzum (literally “contraction”) which states that in order for an infinite, transcendent deity to create a finite world, it must withdraw from a portion of itself, basically providing a space for creation to flow through. I think this is an essential truth about the nature of the creative act, and find tzimtzum to be a compelling metaphor for the withdrawal of ego that is characteristic of creative brain states. The trick is learning how to accomplish this withdrawal. There are as many paths as there are people, and finding the right one is an ongoing challenge that all artists face in one form or another.

The work is never done. But the act of approaching the problem with honesty and humility makes every moment of practice a little window on eternity.

This essay was originally published in La Especial Norte #3, Feb. 2009.

__________________________________________________________________

As David pointed out to me after my essay had already gone to print, the ego withdrawal that I liken to tzimtzum also bears a resemblance to the Taoist principle of wu wei which I understand, with apologies to Kenny Rogers, as a sort of metaphysical “know when to hold ’em.” I think this is a great observation and every bit as useful. Last week Jen Graves (who was at the time also turning her attention to neuroaesthetics) also pointed me in the direction of a book that seems like it might just be the missing link in the connections I’ve made: Lawrence Weschler’s Everything That Rises: A Book of Convergences. I’m quickly realizing that this essay only scratches the surface of a fertile subject that I will have to turn my attention to in future posts, and I welcome more suggestions and associations.